An exhibition curated by Oliver Ressler

“Overground Resistance”, frei_raum Q21 exhibition space, Vienna (AT), 26.08. – 21.11.2021

“Flood Tide of Resistance”, NeMe Arts Centre, Limassol (CY), 07.10. – 04.11.2022

“Overground Resistance. Resistencias a la luz del sol”, CAC Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Quito, Quito (EC), 23.11.2022 – 26.02.2023

Extreme weather conditions have become the global norm. Forests are burning in Brazil and Siberia, permafrost soils are thawing, polar ice and glaciers melt, drought strikes once fertile regions, plant and animal species are becoming extinct on a massive scale. Yet even as the impact of climate breakdown comes to be felt everywhere, government climate policy worldwide is woefully inadequate to the urgency of the crisis. States prefer not to act at all: when forced, they act on a symbolic level at most. On one day they declare a climate emergency; the next day they still sponsor fossil-fueled energy, building freeways, airports and gas pipelines, enclosing territory on whatever scale the projects demand.

This cynical spectacle contributes nothing to planetary survival. What is urgently needed instead is decarbonization of the world economy, total reorganization of trade, food production, labor and housing, plus drastically increased taxation of climate-destructive modes of transport and forms of production that squander resources. The overall social focus must be shifted from growth and profit towards resource conservation, preservation of livelihoods, climate justice and global redistribution.

Climate justice movements worldwide are the most serious and significant drivers of this socially necessary change. The past 25 years of UN climate negotiation have led to no reduction of global carbon emissions whatsoever. Meanwhile, extra-parliamentary and horizontally organized social movements have never relented in their pressure on states to end the fossil fuel economy outright and ensure swift transition to a carbon-neutral society. The movements’ blockade of German lignite mines played crucial part in the decision of that country’s government to phase out the use of coal (although the 2038 exit date announced is too late). Were it not for the years of implacable pressure from Indigenous American Water Protectors, US President Joe Biden would likely never have revoked Federal approval of the Keystone XL tar sands oil pipeline.

Historically, resistance has often been organized “underground” by partisans or extra-parliamentary groups. Climate activism, by contrast, is coming “overground” on a massive scale, despite often crossing the boundaries of what is considered “legal”. The worldwide scope and visibility of the movement reflect the terrifying global scale of the threat and also the unprecedented social breadth and depth of collective determination to counteract it.

To tackle a crisis that is deeply interconnected with the racist, sexist, colonial, and authoritarian foundations of our societies, the climate justice movements’ future lies in becoming intersectional, to transcend what Nancy Fraser described as “merely environmental”: “Addressing the full extent of our general crisis, it must connect its ecological diagnosis to other vital concerns – including livelihood insecurity and denial of labour rights; public disinvestment from social reproduction and chronic undervaluation of carework; ethno-racial-imperial oppression and gender and sex domination; dispossession, expulsion and exclusion of migrants; militarization, political authoritarianism and police brutality. These concerns are intertwined with and exacerbated by climate change”(1).

Millions of people determined to prevent total planetary climate collapse – to preserve the Earth as habitat for future generations – are joining the climate justice movement and collectively taking action. This is also true of many artists, more and more of whom have shown over the last few years that they no longer regard climate change merely as “subject matter” for their works.

This exhibition brings together artists who produce their works in dialogue with the climate justice movements in which they consider themselves participants.

The range of strategies and approaches to be seen here is remarkable.

Some of the artists work on tactical tools for use in public actions. The inflatable cubes of Tools for Action, for instance, assure activists of visibility and can be used as physical barriers in confrontations with police.

Jay Jordan and Isabelle Frémeaux of the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination organized the “Climate Games” event during the Paris COP21 conference of December 2015. The forms of action developed shaped the climate

justice movement’s appearance. In a film shown in the exhibition (2), John Jordan describes artists’ role as one of involvement in the social movements that also constitute their material. Boundaries between art and activism dissolve altogether in this practice. Jordan and Frémeaux live in the autonomous zone ZAD, which formed during resistance to an airport development project near Nantes in France. This is the starting point for a film in the exhibition, “Notre Flamme Des Landes: The Illegal Lighthouse Against an Airport and its World” (2018).

The Natural History Museum is a mobile pop-up-museum founded in 2014 by the Not an Alternative collective, whose independent campaigns are often undertaken conjointly with Indigenous activists or under-represented communities. One focus (among others) is oil industry sponsorship and its role in deciding what is shown in museums, how those works are presented, and what will be excluded altogether. The two videos by The Natural History Museum in the exhibition examine the Houston Museum of Natural Sciences and its sponsors.

Artists producing posters and other such practically useful materials contribute something important to all social movements. Lakota Nation artist Gilbert Kills Pretty Enemy III has produced numerous posters for the protests of Indigenous Water Protectors against the Standing Rock pipeline in North Dakota. UK artist Noel Douglas has been making political posters like “No Breathing Space” (2020, featured in the exhibition) for years. Sometimes these might show up in London public advertising lightboxes regardless of official approval.

Tiago de Aragão produces films of outstanding artistic merit as a participant in the struggles of Indigenous communities in Brazil against the destruction of their livelihoods, such as “Entre Parentes” (2018) about the indigenous protest camp Acampamento Terra Livre in Brasilia.

Mapuche filmmaker Francisco Huichaqueo discusses the war against Indigenous populations in the South of Chile, who experience Pinochet’s neoliberal experiment as continuation of colonial occupation and genocidal atrocities since the 16th century. In the experimental film Mencer: Ñi Pewma (2011), the supernatural of Mapuche symbolism is positioned against the monocultural pine and eucalyptus plantations.

In their film “Rise: From One Island to Another” (2018) Aka Niviâna and Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner show the mutual dependence of their respective home territories Greenland and the Marshall Islands, in both of which melting ice floes and the rising sea levels resulting constitute immediate reality.

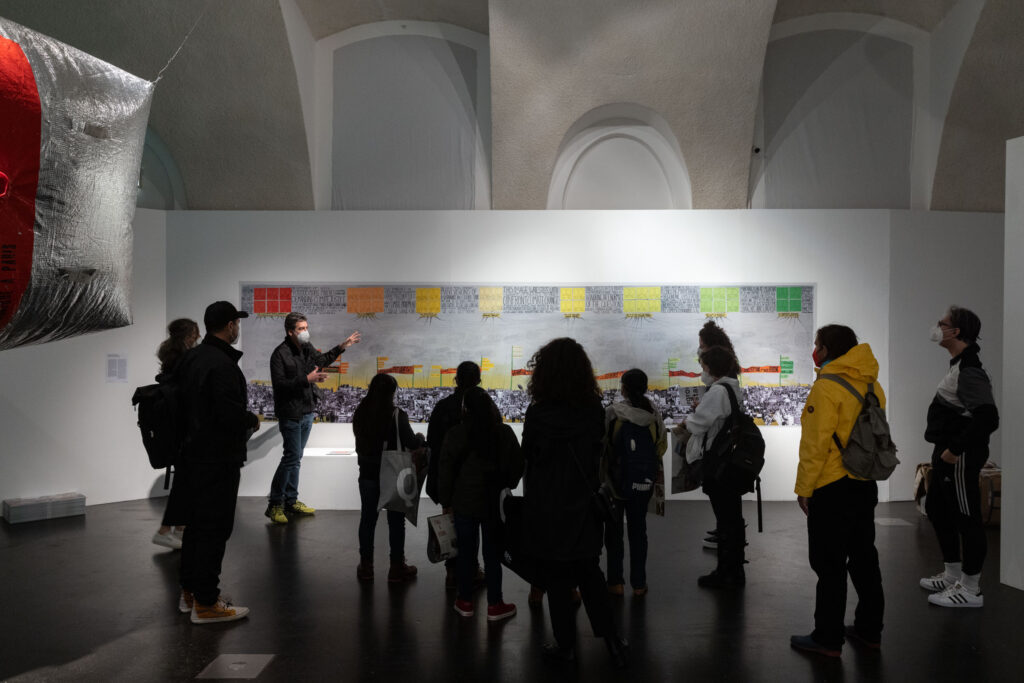

Rachel Schragis, a community organizer and coordinator of climate activism in Brooklyn, NYC, vividly conveys insights obtained through this engagement in her large-format flowchart “Confronting the Climate”(2016). This work emerged from her organizing activity for the New York “People’s Climate March” of 2014.

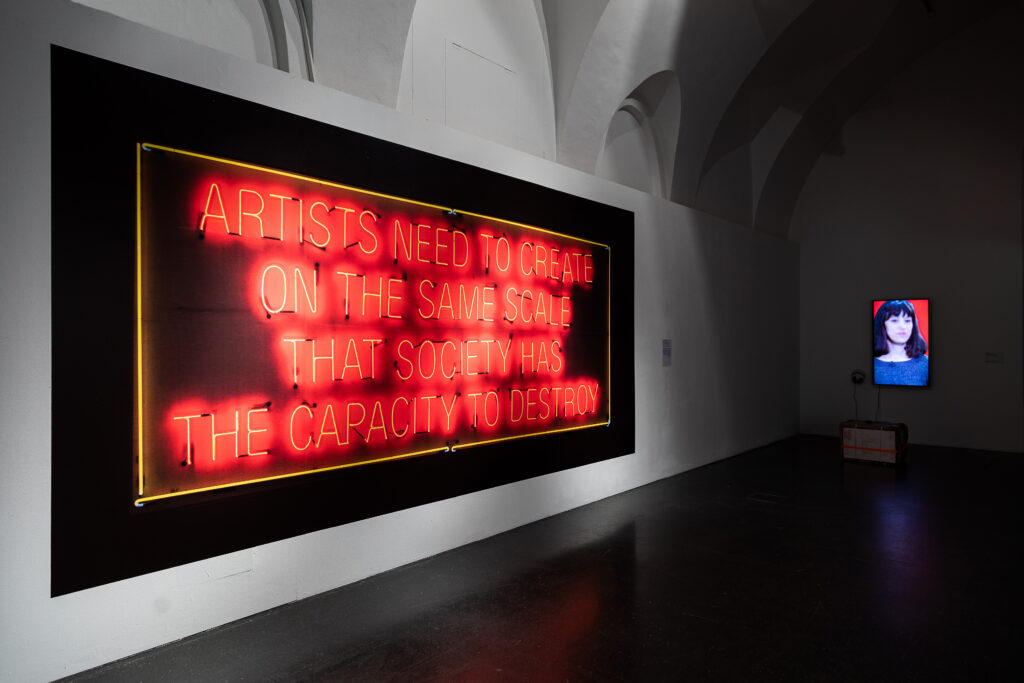

The provocative text-based work “Artists Must Create on the Same Scale that Society Has the Capacity to Destroy” by Lauren Bon and the Metabolic Studio confirms once and for all that nothing in this exhibition is a matter depiction or documentation in a pure sense. Rather, it is all about establishing relationships with social movements in which the artists and cultural producers are actively engaged.

Jonas Staal’s “Climate Propagandas, Video Study” (2020) shows how the climate crisis is interpreted and weaponized within four ideological discourses, namely liberal, libertarian, conspiracist and eco-fascist climate propaganda. Their spread and influence confirm the urgent need to intensify the struggle for intergenerational climate justice through planetary redistribution, colonial reparations and the construction of comradely ecosystems between human and other-than-human proletarians. This struggle articulates, in Staal’s words, a “deep future climate propaganda.”

In the context of this exhibition, Seday’s paintings on display windows of banks point to the financial sources of a climate disaster driven by fossil-fuel capital. Over the past six years the anonymous artist has vandalized more than 100 French banks with his multi-color varnish paintings, mimicking Jackson Pollock’s all-over style and leaving a symbolic trace on the financial institutions.

A number of exhibitions within the last few years have addressed climate breakdown. Most, as in the case of the 2020 Taipei Biennial curated by Bruno Latour and Martin Guinard, have emphasized aesthetic experience, setting activist strategies aside (3).

The exhibition cycle “Overground Resistance” by contrast, appears to be the first art exhibition worldwide to focus directly on climate activism.

(1) Nancy Fraser, Climates of Capital, New Left Review 127, January–February 2021

(2) Oliver Ressler, Barricade Cultures of the Future, 4K, 2021

(3) “Many of the works we gathered are not ‘activist’ in the sense that they don’t put as their first agenda a call to action, but rather propose a strong aesthetic experience.” Bruno Latour and Martin Guinard, cited in: Naomi Rea, “To Explore the Impact of Climate Change on Culture, the Curators of the Taipei Biennial Transformed Their Venue Into a Planetarium”, Artnet, December 2, 2020

“Overground Resistance”, frei_raum Q21 exhibition space, Vienna, 2021

Artists:

Tiago de Aragão (BR)

Lauren Bon and the Metabolic Studio (US)

Noel Douglas (UK)

Francisco Huichaqueo (Mapuche Nation/CL)

Gilbert Kills Pretty Enemy III (Hunkpapa Lakota of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe/US)

Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner (Marshall Islands) & Aka Niviâna (Greenland)

Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (FR)

The Natural History Museum (US)

Oliver Ressler (AT)

Rachel Schragis (US)

Seday (FR)

Jonas Staal (NL)

Tools for Action (HU/NL)

“Flood Tide of Resistance”, NeMe Arts Centre, Limassol (CY), 2022

Artists:

Tiago de Aragão (BR)

Lauren Bon and the Metabolic Studio (US)

Noel Douglas (UK)

Francisco Huichaqueo (Mapuche Nation/CL)

Gilbert Kills Pretty Enemy III (Hunkpapa Lakota of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe/US)

Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner (Marshall Islands) & Aka Niviâna (Greenland)

Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (FR)

The Natural History Museum (US)

Oliver Ressler (AT)

Enar de Dios Rodríguez (ES)

Theo Prodromidis (GR)

Rachel Schragis (US)

Seday (FR)

Jonas Staal (NL)

Tools for Action (HU/NL)

No Grandi Navi (IT)

“Overground Resistance. Resistencias a la luz del sol”, CAC Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Quito, Quito (EC), 2022

Artists:

Tiago de Aragão (BR)

Arts for the Commons – A4C (IT/EC)

Lauren Bon and the Metabolic Studio (US)

Noel Douglas (UK)

Francisco Huichaqueo (Mapuche Nation/CL)

Gilbert Kills Pretty Enemy III (Hunkpapa Lakota of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe/US)

Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner (Marshall Islands) & Aka Niviâna (Greenland)

Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (FR)

Boloh Miranda Izquierdo (EC) & Sofia Acosta Varea (EC)

The Natural History Museum (US)

Oliver Ressler (AT)

Rachel Schragis (US)

Seday (FR)

Jonas Staal (NL) Tools for Action (HU/NL)